Africa

What Silicon Valley could learn from Nigeria’s Igbo entrepreneurs

- Photographer alleges he was forced to watch Megan Thee Stallion have sex and was unfairly fired - April 25, 2024

- Navigating Bias and Ethics in AI-Powered Cybersecurity: The BRACE Framework Approach - April 17, 2024

- Body of O.J. Simpson to be cremated this week; brain will not be studied for CTE - April 16, 2024

Africa

Donors raise more than 2 billion euros for Sudan aid a year into war

- Photographer alleges he was forced to watch Megan Thee Stallion have sex and was unfairly fired - April 25, 2024

- Navigating Bias and Ethics in AI-Powered Cybersecurity: The BRACE Framework Approach - April 17, 2024

- Body of O.J. Simpson to be cremated this week; brain will not be studied for CTE - April 16, 2024

Africa

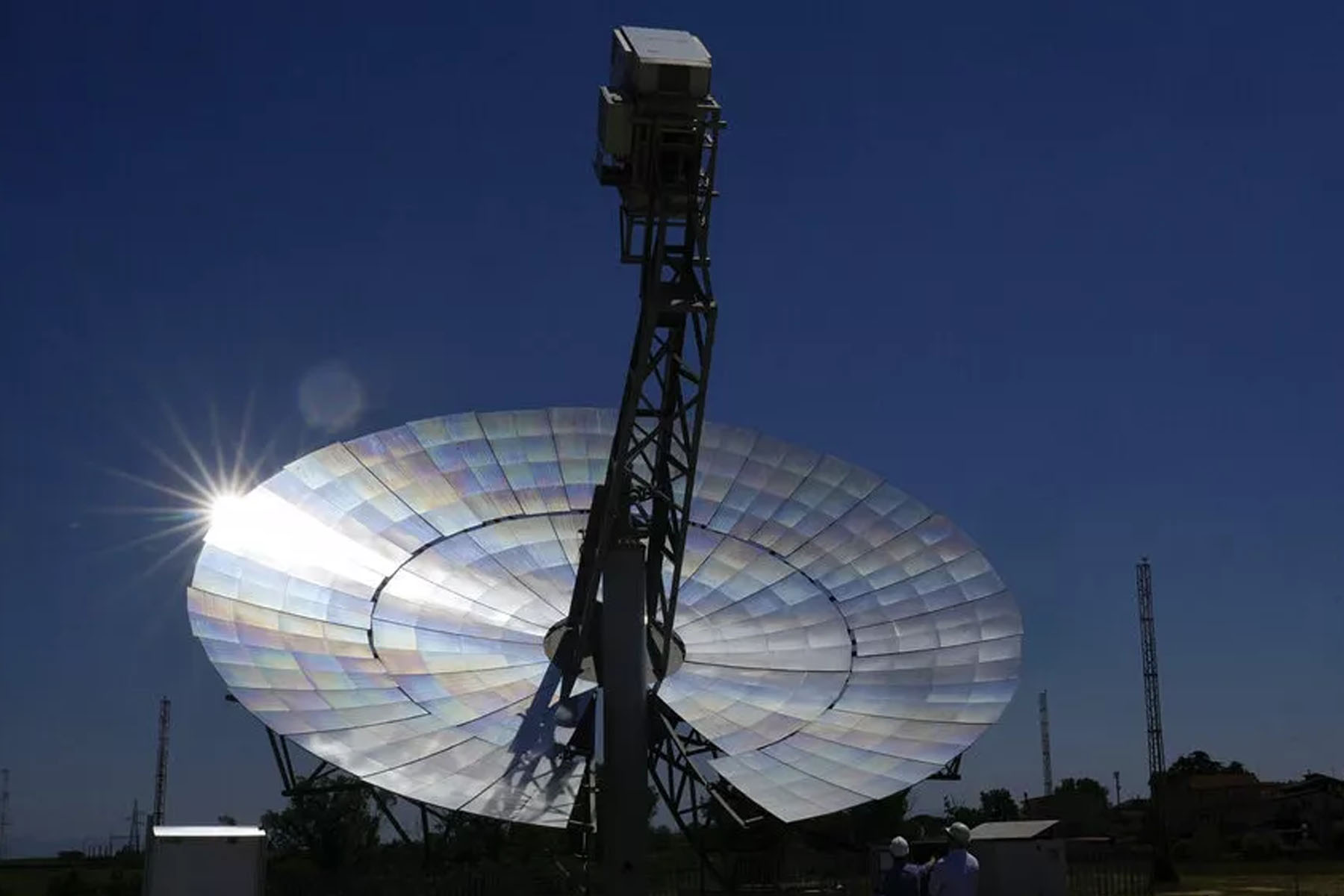

SA users of Starlink will be cut off at the end of the month

Starlink users in South Africa are facing a major setback as the satellite internet service provider has issued a warning that their services will be terminated by the end of the month.

In an email sent to many South African users, Starlink stated that their internet access will cease on April 30 due to violation of its terms and conditions.

The email emphasized that using Starlink kits outside of designated areas, as indicated on the Starlink Availability Map, is against their terms. Consequently, users will only be able to access their Starlink account for updates after the termination.

Starlink, a company owned by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, operates a fleet of low earth orbit satellites that offer high-speed internet globally. Despite its potential to revolutionize connectivity, Starlink has been unable to obtain a license to operate in South Africa from the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (Icasa).

Icasa’s requirements mandate that any applicant must have 30% ownership from historically disadvantaged groups to be considered for a license. However, many in South Africa resorted to creative methods to access Starlink services, including purchasing roaming packages from countries where Starlink is licensed.

However, Icasa clarified in a government gazette last November that using Starlink in this manner is illegal. Additionally, Starlink itself stated in the recent email to users that the ‘Mobile – Regional’ plans are meant for temporary travel and transit, not permanent use in a location. Continuous use of these plans outside the country where service was ordered will result in service restriction.

Starlink advised those interested in making its services available in their region to contact local authorities.

- Photographer alleges he was forced to watch Megan Thee Stallion have sex and was unfairly fired - April 25, 2024

- Navigating Bias and Ethics in AI-Powered Cybersecurity: The BRACE Framework Approach - April 17, 2024

- Body of O.J. Simpson to be cremated this week; brain will not be studied for CTE - April 16, 2024

Africa

Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso agree to create a joint force to fight worsening violence

BAMAKO, Mali (AP) — A joint security force announced by the juntas ruling Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso to fight the worsening extremist violence in their Sahel region countries faces a number of challenges that cast doubt on its effectiveness, analysts said Thursday.

Niger’s top military chief, Brig. Gen. Moussa Salaou Barmou said in a statement after meeting with his counterparts Wednesday that the joint force would be “operational as soon as possible to meet the security challenges in our area.”

The announcement is the latest in a series of actions taken by the three countries to strike a more independent path away from regional and international allies since the region experienced a string of coups — the most recent in Niger in July last year.

They have already formed a security alliance after severing military ties with neighbors and European nations such as France and turning to Russia — already present in parts of the Sahel — for support.

Barmou did not give details about the operation of the force, which he referred to as an “operational concept that will enable us to achieve our defence and security objectives.”

Although the militaries had promised to end the insurgencies in their territories after deposing their respective elected governments, conflict analysts say the violence has instead worsened under their regimes. They all share borders in the conflict-hit Sahel region and their security forces fighting jihadi violence are overstretched.

The effectiveness of their security alliance would depend not just on their resources but on external support, said Bedr Issa, an independent analyst who researches the conflict in the Sahel.

The three regimes are also “very fragile,” James Barnett, a researcher specializing in West Africa at the U.S.-based Hudson Institute, said, raising doubts about their capacity to work together.

“They’ve come to power through coups, they are likely facing a high risk of coups themselves, so it is hard to build a stable security framework when the foundation of each individual regime is shaky,” said Barnett.

—-

Associated Press writer Chinedu Asadu in Abuja, Nigeria contributed.

- Photographer alleges he was forced to watch Megan Thee Stallion have sex and was unfairly fired - April 25, 2024

- Navigating Bias and Ethics in AI-Powered Cybersecurity: The BRACE Framework Approach - April 17, 2024

- Body of O.J. Simpson to be cremated this week; brain will not be studied for CTE - April 16, 2024

-

Column1 week ago

Column1 week agoNavigating Bias and Ethics in AI-Powered Cybersecurity: The BRACE Framework Approach

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoTrump trial update: Trump rebuked by judge for speaking during jury selection — and 7 jurors are seated

-

Lifestyle1 week ago

Lifestyle1 week agoBody of O.J. Simpson to be cremated this week; brain will not be studied for CTE

-

Education1 week ago

Education1 week ago11 Communication Students Awarded Scholarships at TSU’s Commweek

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoDonors raise more than 2 billion euros for Sudan aid a year into war

-

Africa1 week ago

Africa1 week agoSA users of Starlink will be cut off at the end of the month

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNigeria: chibok abduction anniversary spurs demands for justice

-

News1 week ago

News1 week agoNigeria suspends permit of 3 private jet operators