Education

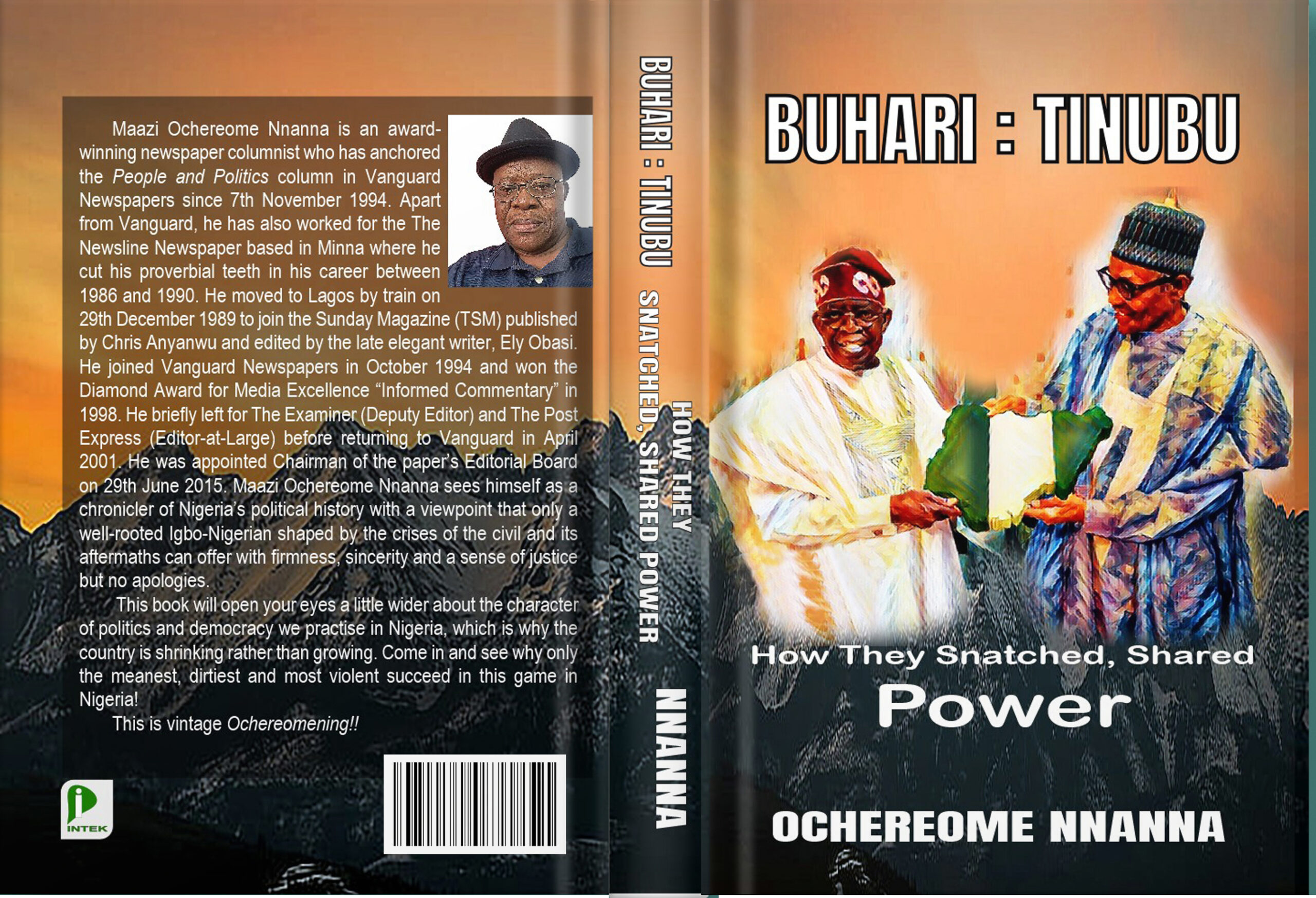

New Book: “Buhari:Tinubu – How they snatched, shared power”

- JD Vance breaks polling records in the worst way - July 25, 2024

- Donald Trump’s Losing Election Poll for First Time in Over a Month - July 25, 2024

- FBI Is Not Fully Convinced Trump Was Struck by a Bullet - July 25, 2024

Education

Nigerian Appointed First Female Chancellor of the University of Birmingham

Nigerian, Sandie Okoro OBE has been appointed by the University of Birmingham as its new Chancellor. With her appointment, she becomes the first female to be appointed chancellor by the university since its establishment over 100 years ago.

Okoro, a lawyer and diversity expert is currently the Group General Counsel of Standard Chartered where she leads the Bank’s Legal, Group Corporate Secretariat, and Shared Investigative Services functions.

Okoro will succeed Lord Bilimoria of Chelse CBE who will step down after 10 years in the role on July 10.

Speaking on her appointment, she said:

I am truly honoured and delighted to be appointed Chancellor. It’s a fantastic opportunity for me to give a little something back to the amazing University that has given so very much to me and my family.

“The wonderful University of Birmingham is the alma mater to three generations of the Okoros, my mum, me and my son. So my connection to it is very special indeed. I have followed the University’s outstanding progress very closely since my days there as a student on a full grant back in the 1980s – its dedication to impactful research, its focus on creating an inclusive environment for talented, minority students and educational excellence are themes very close to my heart.

Okoro, an alumna of the University of Birmingham is a graduate of Law and Politics qualifying as a barrister at the City, University of London. She has held roles as Head of Legal for Corporate Services at Schroders, Global General Counsel at Barings, and General Counsel for HSBC Global Asset Management. Okoro was also Senior Vice-President and General Counsel, and Vice-President for Compliance, for the World Bank Group.

She is a 2024 officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and an Honorary Bencher of the Middle Temple.

- JD Vance breaks polling records in the worst way - July 25, 2024

- Donald Trump’s Losing Election Poll for First Time in Over a Month - July 25, 2024

- FBI Is Not Fully Convinced Trump Was Struck by a Bullet - July 25, 2024

Education

Black teen in Georgia awarded over $14m in scholarships, accepted at 231 colleges

An 18-year-old low-income student has just defied the odds by achieving an extraordinary feat in her pursuit of higher education.

Madison Crowell, from Hinesville, Georgia secured her acceptance into an astounding 231 colleges and universities across the nation. She has also been awarded an impressive $14.7 million in scholarships to support her academic journey.

Crowell’s remarkable achievement is not only a testament to her academic prowess but also to her unwavering determination and resilience in the face of adversity.

Growing up in a low-income community, she explained she was driven by a desire to showcase the possibilities available to students like herself.

“I wanted to apply to as many schools as I did because I want to show the kids here in Liberty County that it’s possible to get accepted into schools […] that you think might be out of your reach but is definitely in reach,” she told Good Morning America.

Despite facing challenges along the way, Crowell remained steadfast in her pursuit of higher education. With the support of her parents, Sgt. 1st Class Delando Langley and Melissa Langley, she embarked on college tours and road trips from a young age, preparing herself for the journey ahead.

Now, as she prepares to embark on her college adventure, Crowell’s hard work and determination have paid off. She has chosen to attend High Point University in High Point, North Carolina, where she will pursue her academic aspirations under a full tuition scholarship.

In response to her incredible achievement, High Point University President Dr. Nido Qubein extended a warm welcome to Crowell, recognizing her potential to achieve greatness.

“We welcome you to our HPU family”, he said. “You’re going to do exceptional things right here at The Premier Life Skills University, where we call everybody to be extraordinary. The sky is not the limit […] and when you come here to High Point University, we know you’ll be a leader. We know you’ll make amazing things happen. We’re here to resource her, cheer you on and celebrate you victory.”

Despite her overwhelming number of acceptances, Cromwell revealed she hadn’t been accepted to other top schools and urged other students to persevere.

“I know what it’s like to be deferred from a dream school and you don’t know if you’re gonna get the chance to apply again or you’re not going to be accepted again,” she said. “I just want to make it known that nothing is impossible and that the sky is not the limit and that you want to keep pushing for greatness.”

- JD Vance breaks polling records in the worst way - July 25, 2024

- Donald Trump’s Losing Election Poll for First Time in Over a Month - July 25, 2024

- FBI Is Not Fully Convinced Trump Was Struck by a Bullet - July 25, 2024

Education

11 Communication Students Awarded Scholarships at TSU’s Commweek

Each student received $1,000 through the SOC scholarship initiative.

Scholarships alleviate financial stress and contribute to academic success, diversity, and equitable access to education. They are a valuable resource for college students, opening doors that might otherwise remain closed due to financial barriers. The 2024 Commweek – the 42nd Intercultural and Communication Conference of the School of Communication (SOC) at Texas Southern University ended Friday, April 12 with a cheerful outcome. 11 communication students walked away with a fat check as beneficiaries of the SOC Commweek Scholarship initiative.

The recipients of the 2024 Commweek scholarships are Christopher Jarmon, Rachel Frank, Benjamin Clark, Racheal Lewis, Briannah Dilworth, Courtney Roberts, Precious Johnson, Douglas Gordon, Briana Williams, Zoria Goodley, and Erin Slaughter. Each student received $1,000 from the SOC scholarship initiative, aimed at helping students overcome financial obstacles while pursuing their academic goals. The funds can be used to cover tuition, textbooks, other educational expenses, and living costs like housing, transportation, and food.

Dr. Chris Ulasi, the Interim Dean of the School of Communication, explained that the scholarship funds were made possible through grants and donations from corporate and local businesses. These contributions were specifically designated for talented and economically disadvantaged students within the School of Communication. “Many of these students rely on financial aid to support their education. Therefore, we prioritized collaborating with private and corporate partners to support this initiative,” Dr. Ulasi stated.

Themed “Amplifying Diverse Voices in Media and Communication,” Commweek kicked off on April 8 and concluded with an Awards Gala on Friday, April 12, 2024, where scholarships were presented. Throughout the week, scholars, students, professionals, and civic leaders engaged in discussions on topics with cultural, political, economic, and social significance, as well as communication dynamics.

The School of Communication (SOC) at Texas Southern University is a dynamic academic institution that fosters interdisciplinary learning. With four departments and two graduate programs – Communication Studies, Entertainment Recording Industry Management (ERIM), Journalism, and Radio, Television, and Film (RTF), along with a Master of Arts (MA) in Communication and Master of Arts (M.A.) in Professional Communication and Digital Media (PCDM) – SOC has been a leader in training culturally responsive professionals and scholars for nearly five decades. Graduates are equipped to navigate diverse urban and international environments with inclusivity and a deep understanding of historical context.

- JD Vance breaks polling records in the worst way - July 25, 2024

- Donald Trump’s Losing Election Poll for First Time in Over a Month - July 25, 2024

- FBI Is Not Fully Convinced Trump Was Struck by a Bullet - July 25, 2024

-

Anthony Obi Ogbo2 days ago

Anthony Obi Ogbo2 days agoSylvester Turner Should Cancel His Bid for Late Jackson Lee’s Congressional Seat

-

Anthony Obi Ogbo1 week ago

Anthony Obi Ogbo1 week agoWas Trump’s Assassin unstoppable because he was White?

-

Column2 days ago

Column2 days agoAdvocating for Reviving the 1960s Constitution Toward Creating a United Region of Nigeria

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoOMG: Donald Trump Shooter Was a Registered Republican

-

Lifestyle2 weeks ago

Lifestyle2 weeks agoEddie Murphy and Paige Butcher Are Married! Inside Their Private Caribbean Wedding

-

News2 weeks ago

News2 weeks agoDonald Trump survives assassination attempt; FBI identifies shooter

-

Houston2 weeks ago

Houston2 weeks agoHurricane Beryl: Wazobia postpones family fanfare slated for this weekend

-

Lifestyle2 weeks ago

Lifestyle2 weeks agoYale honors a young Black scientist after a neighbor falsely reported the 9-year-old to the police