Nigeria

Schooling in Nigeria a scam?

- Burna Boy, the Spotlight, and the Cost of Arrogance - November 27, 2025

- Billionaires Conclave USA Brings Career Wealth Masterclass to Houston with Dr. Olumide Emmanuel - July 12, 2025

- OPINION: What Has Quality Got to Do With Soludo’s Made-in-Anambra Brands - February 5, 2022

Africa

Nigeria–Burkina Faso Rift: Military Power, Mistrust, and a Region Out of Balance

The brief detention of a Nigerian Air Force C-130 Hercules aircraft and its crew in Burkina Faso may have ended quietly, but it exposed a deeper rift shaped by mistrust, insecurity, and uneven military power in West Africa. What was officially a technical emergency landing quickly became a diplomatic and security flashpoint, reflecting not hostility between equals, but anxiety between unequally matched states navigating very different political realities.

On December 8, 2025, the Nigerian Air Force transport aircraft made an unscheduled landing in Bobo-Dioulasso while en route to Portugal. Nigerian authorities described the stop as a precautionary response to a technical fault—standard procedure under international aviation and military safety protocols. Burkina Faso acknowledged the emergency landing but emphasized that the aircraft had violated its airspace, prompting the temporary detention of 11 Nigerian personnel while investigations and repairs were conducted. Within days, the crew and aircraft were released, underscoring a professional, if tense, resolution.

Yet the symbolism mattered. In a Sahel region gripped by coups, insurgencies, and fragile legitimacy, airspace is not merely technical—it is political. Burkina Faso’s reaction reflected a state on edge, hyper-vigilant about sovereignty amid persistent internal threats. Nigeria’s response, measured and restrained, reflected confidence rooted in capacity.

The military imbalance between the two countries is stark. Nigeria fields one of Africa’s most formidable armed forces, with a tri-service structure that includes a large, well-equipped air force, a dominant regional navy, and a sizable army capable of sustained operations. The Nigerian Air Force operates fighter jets such as the JF-17 and F-7Ni, as well as A-29 Super Tucanos for counterinsurgency operations, heavy transport aircraft like the C-130, and an extensive helicopter fleet. This force is designed not only for internal security but for regional power projection and multinational operations.

Burkina Faso’s military, by contrast, is compact and narrowly focused. Its air arm relies on a limited number of light attack aircraft, including Super Tucanos, and a small helicopter fleet primarily dedicated to internal counterinsurgency. There is no navy, no strategic airlift capacity comparable to Nigeria’s, and limited logistical depth. The Burkinabè military is stretched thin, fighting multiple insurgent groups while also managing the political consequences of repeated military takeovers.

This imbalance shapes behavior. Nigeria’s military posture is institutional, outward-looking, and anchored in regional frameworks such as ECOWAS. Burkina Faso’s posture is defensive, reactive, and inward-facing. Where Nigeria seeks stability through deterrence and cooperation, Burkina Faso seeks survival amid constant internal pressure. That difference explains why a technical landing could be perceived as a “serious security breach” rather than a routine aviation incident.

The incident also illuminates why Burkina Faso continues to struggle to regain political balance. Repeated coups have eroded civilian institutions, fractured command structures, and blurred the line between governance and militarization. The armed forces are not just security actors; they are political stakeholders. This creates a cycle where insecurity justifies military rule, and military rule deepens insecurity by weakening democratic legitimacy and regional trust.

Nigeria, despite its own security challenges, has managed to avoid this spiral. Civilian control of the military remains intact, democratic transitions—however imperfect—continue, and its armed forces operate within a clearer constitutional framework. This stability enhances Nigeria’s regional credibility and amplifies its military superiority beyond hardware alone.

The C-130 episode did not escalate into confrontation precisely because of this asymmetry. Burkina Faso could assert sovereignty, but not sustain defiance. Nigeria could have asserted its capability, but chose restraint. In the end, professionalism prevailed.

Still, the rift lingers. It is not about one aircraft or one landing, but about two countries moving in different strategic directions. Nigeria stands as a regional anchor with superior military power and institutional depth. Burkina Faso remains a state searching for equilibrium—politically fragile, militarily constrained, and acutely sensitive to every perceived threat from the skies above.

- Burna Boy, the Spotlight, and the Cost of Arrogance - November 27, 2025

- Billionaires Conclave USA Brings Career Wealth Masterclass to Houston with Dr. Olumide Emmanuel - July 12, 2025

- OPINION: What Has Quality Got to Do With Soludo’s Made-in-Anambra Brands - February 5, 2022

Lifestyle

Kaduna Governor Commissions Nigeria’s First 100-Building Prefabricated Housing Estate

Kaduna, Nigeria – November 6, 2025 — In a major milestone for Nigeria’s housing sector, the Governor of Kaduna State has commissioned a 100-unit mass housing estate developed by Family Homes and executed by Karmod Nigeria, marking the first-ever large-scale prefabricated housing project in the country.

Completed in under six months, the innovative project demonstrates the power of modern prefabricated construction to deliver high-quality, affordable homes at record speed — a sharp contrast to traditional building methods that often take years.

Each of the 100 units in the estate is designed for a lifespan exceeding 50 years with routine maintenance. The development features tarred access roads, efficient drainage systems, clean water supply, and steady electricity, ensuring a modern and comfortable living environment for residents.

According to Family Homes, the project represents a new era in Nigeria’s mass housing delivery, proving that cutting-edge technology can accelerate the provision of sustainable and cost-effective homes for Nigerians.

“With prefabricated technology, we can drastically reduce construction time while maintaining top-quality standards,” said a spokesperson for Family Homes. “This project is a clear demonstration of what’s possible when innovation meets commitment to solving Nigeria’s housing deficit.”

Reinforcing this commitment, Governor Uba Sani of Kaduna State emphasized the alignment between the initiative and the state’s broader vision for affordable housing.

“The Family Homes Funds Social Housing Project aligns with our administration’s commitment to the provision of affordable houses for Kaduna State citizens. Access to safe, affordable and secure housing is the foundation of human dignity. We have been partnering with local and international investors to frontally address our housing deficit,” he said.

Also speaking at the event, Mr. Ademola Adebise, Chairman of Family Homes Funds Limited, noted that the project embodies inclusivity and social progress.

“The Social Housing Project also reflects our shared vision of inclusive growth, where affordable housing becomes a foundation for economic participation and improved quality of life.”

Karmod Nigeria, the technical partner behind the project, utilized its extensive expertise in prefabricated technology to localize the process, employing local artisans and materials to enhance community participation and job creation.

Industry experts have described the Kaduna project as a blueprint for future housing initiatives nationwide, capable of addressing the country’s housing shortfall more efficiently and sustainably.

With this pioneering development, Kaduna State takes a leading role in introducing modern housing technologies that promise to reshape Nigeria’s urban landscape.

- Burna Boy, the Spotlight, and the Cost of Arrogance - November 27, 2025

- Billionaires Conclave USA Brings Career Wealth Masterclass to Houston with Dr. Olumide Emmanuel - July 12, 2025

- OPINION: What Has Quality Got to Do With Soludo’s Made-in-Anambra Brands - February 5, 2022

Books

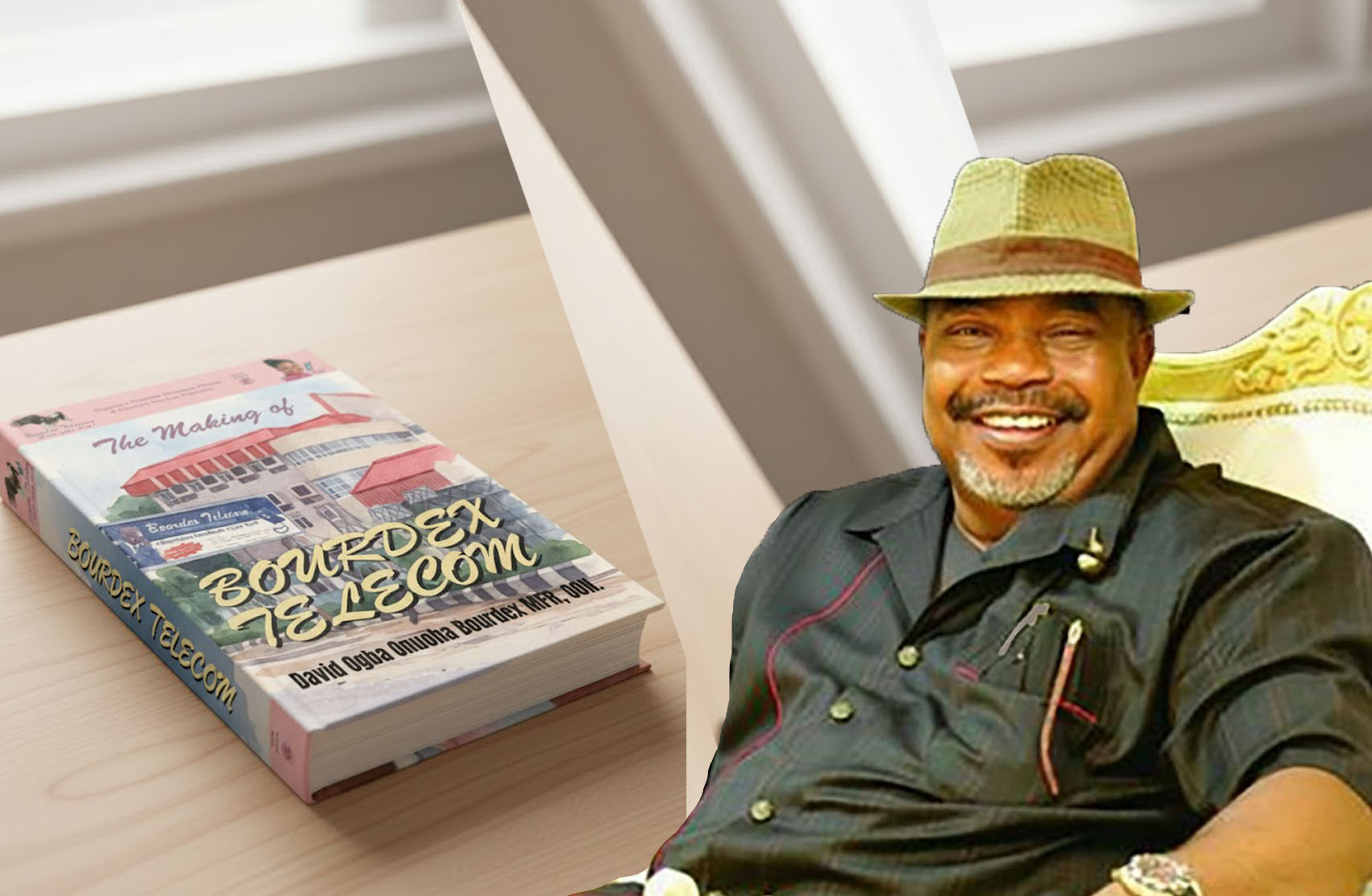

The Pioneer’s Burden: Building the First Private Network in a Vacuum of Power

- Book Title: The Making of Bourdex Telecom

- Author: David Ogba Onuoha Bourdex

- Publishers: Bourdex

- Reviewer: Emeaba Emeaba

- Pages: 127

In the history of Nigerian entrepreneurship, stories of audacity often begin with frustration. A man waits hours in a dimly lit government office to place a single overseas call, his ambitions held hostage by bureaucracy. From that moment of exasperation, an empire begins. Such is the animating pulse of The Making of Bourdex Telecom, David Ogba Onuoha Bourdex’s sweeping autobiographical account of one man’s effort to connect the disconnected and to rewrite the telecommunications map of Eastern Nigeria.

At once memoir, corporate history, and national parable, the book reconstructs the emergence of Bourdex Telecommunications Limited—the first indigenous private telecom provider in Nigeria’s South-East and South-South regions—against a backdrop of inefficiency, corruption, and infrastructural neglect. Its author, a businessman turned visionary, narrates not merely how a company was built but how a new horizon of possibility was forced open in a society long accustomed to closed doors.

Bourdex begins with a stark diagnosis of pre-deregulation Nigeria: a nation of over 120 million people served by fewer than a million telephone lines. Through a mix of statistical precision and personal recollection, he paints a portrait of communication as privilege, not right—of entire regions condemned to silence by state monopoly. His storytelling thrives in such contrasts: the entrepreneur sleeping upright in Lagos’s NET building to place an international call; the Italian businessman in Milan conducting deals with two sleek mobile phones. That juxtaposition—between deprivation and effortless connectivity—serves as the book’s moral axis.

From these moments of contrast, Bourdex constructs the founding myth of his enterprise. What began as an irritation became a revelation, then a crusade. “I saw a people left behind,” he writes, “a region cut off while others dialed into the future.” His insistence on framing technology as a means of liberation rather than profit underscores the moral ambition that threads through the book. The Making of Bourdex Telecom reads not like a manual of business success but like an ethical manifesto: to build not simply for gain, but for dignity.

As the chapters unfold, Bourdex’s narrative oscillates between vivid personal storytelling and granular technical detail. He recounts his early business dealings in the 1980s and ’90s, the bureaucratic mazes of NITEL, and the daring pursuit of a telecommunications license under General Sani Abacha’s military government. There is a cinematic quality to his recollections—the tense midnight meetings in Abuja, the coded alliances with military officers, the improbable friendships that turned policy into possibility.

These sections recall Chinua Achebe’s The Trouble with Nigeria in tone and intention: both works diagnose the systemic failures of governance but find redemption in individual initiative. Yet Bourdex’s narrative differs in form. Where Achebe offered moral critique, Bourdex offers demonstration—an anatomy of perseverance in motion. He documents the letters, negotiations, and international correspondences with Harris Canada, showing how an indigenous company emerged through sheer force of will and global collaboration.

Such passages risk overwhelming the reader with acronyms, specifications, and telecom jargon—R2 signaling, SS7 interconnection, E1 circuits—but they also lend the book an authenticity rare in corporate memoirs. What might have been opaque technicalities become, under Bourdex’s hand, instruments of drama. The machinery of communication becomes metaphor: wires and waves as extensions of faith and tenacity.

To situate The Making of Bourdex Telecom within Nigeria’s socio-political history is to confront the paradox of private enterprise under public decay. The book chronicles the twilight of NITEL’s monopoly, the hesitant dawn of deregulation, and the emergence of entrepreneurial actors who filled the void left by government paralysis. In this sense, Bourdex’s story parallels that of other indigenous pioneers—figures such as Mike Adenuga and Jim Ovia—whose ventures in telecommunications and banking transformed the national economy from the late 1990s onward.

Yet Bourdex’s tone is less triumphant than reflective. He does not romanticize deregulation; he portrays it as both opportunity and ordeal. The government’s inertia, the labyrinthine licensing process, and the outright extortion by state agencies form the darker undertones of his tale. His clash with NITEL’s leadership—recounted with controlled indignation—stands as one of the book’s most gripping sequences. When a senior official demanded an illegal payment of ₦20.8 million for interconnection rights, Bourdex’s defiant reply, “You are not God,” rang out like an act of civil disobedience. In such moments, the narrative transcends the genre of business autobiography and enters the moral theatre of national reform. The entrepreneur becomes citizen-prophet, challenging a corrupt establishment with the rhetoric of justice and self-belief. That blending of economic narrative with civic conscience is perhaps the book’s most compelling feature.

Stylistically, The Making of Bourdex Telecom occupies an intriguing space between oral history and polished memoir. The prose is direct, rhythmic, and often sermonic, reflecting its author’s background as both businessman and public speaker. Anecdotes unfold with the cadences of storytelling; sentences sometimes pulse with the energy of spoken word: “Amateurs built the Ark. Professionals built the Titanic.” The repetition of such aphorisms imbues the work with a sense of conviction, though occasionally at the expense of subtlety.

Where the book excels is in its evocation of atmosphere—the dusty highways between Aba and Lagos, the sterile corridors of power in Abuja, the crisp air of Calgary where the author first glimpsed technological modernity. These scenes transform what could have been a linear corporate chronicle into a textured work of memory.

Still, the narrative structure is not without flaws. The absence of an external editor’s restraint is occasionally felt in the pacing; digressions into technical exposition or moral reflection sometimes interrupt narrative flow. Readers accustomed to the concise storytelling of international business memoirs—Phil Knight’s Shoe Dog or Elon Musk’s authorized biography—may find the prose dense in places. Yet such density mirrors the complexity of the terrain Bourdex navigated. His sentences, like his towers, are built from layers of persistence.

Beyond its entrepreneurial chronicle, the book doubles as social history—a record of Eastern Nigeria’s encounter with modernization. The chapters on “The FUTO Boys,” a cadre of young engineers recruited from the Federal University of Technology, Owerri, offer a microcosm of the new Nigerian professional class emerging in the late 1990s: educated, idealistic, and determined to prove that technical expertise could thrive outside the state. Their improvisations—installing antennas by candlelight, building networks amid power outages—embody the collective grit that sustained Bourdex’s vision.

The narrative’s cumulative effect is generational. Through the story of one company, we glimpse a society in transition—from analogue isolation to digital awakening. The book captures that liminal moment when the sound of a dial tone became a symbol of freedom.

Running through The Making of Bourdex Telecom is a persistent theology of success. Bourdex attributes every turn in his journey to divine orchestration: friendships “placed by the Invisible Hand,” setbacks reinterpreted as “divine redirections.” Such language, while characteristic of Nigerian entrepreneurial spirituality, acquires here an almost literary force. It recasts corporate history as providential narrative, where the invisible infrastructure of grace mirrors the visible architecture of towers and transmitters.

For some readers, this piety may feel excessive; yet it provides the emotional coherence of the book. The author’s faith is not ornamental—it is constitutive. Without it, the story of Bourdex Telecom would read as mere ambition. With it, it becomes vocation.

The foreword by Abia State Governor Alex Otti and the preface by former Anambra Governor Peter Obi frame the book as both inspiration and instruction. They read Bourdex’s career as parable: the triumph of private initiative over public inertia. Yet their presence also situates the work within Nigeria’s broader discourse on nation-building. The Making of Bourdex Telecom is not only the autobiography of an entrepreneur; it is a treatise on indigenous agency—on what happens when Africans cease to wait for imported solutions and begin to engineer their own.

In this respect, the book extends its influence beyond its immediate industry. Its lessons—about courage, timing, friendship, and faith—extend to any field where innovation must contend with adversity.

Judged as a work of literature, The Making of Bourdex Telecom is direct and sincere. Its prose favors clarity over ornament, and its authenticity gives the story a compelling sense of truth. Bourdex writes not to embellish, but to bear witness—to a time, a struggle, and a conviction that technology could serve humanity. The result is a hybrid work: part documentary, part sermon, part memoir of enterprise.

As a contribution to Nigerian business literature, it deserves serious attention. Few firsthand accounts capture with such detail the messy birth of private telecommunications in the 1990s—a revolution that reshaped the country’s economic and social fabric. In its pages, we hear both the crackle of the first connected call and the larger resonance of a people finding their voice.

Bourdex’s central message endures: progress begins when frustration becomes purpose. His journey from the backrooms of NITEL to the boardrooms of international telecoms is not merely personal triumph; it is a chapter in Nigeria’s unfinished story of modernization.

In the end, The Making of Bourdex Telecom stands as more than the history of a company. It is an ode to enterprise as nation-building, and to the stubborn optimism of those who refuse to let silence define them.

See the book on Amazon: >>>>>

_________

♦ Dr. Emeaba, the author of “A Dictionary of Literature,” writes dime novels in the style of the Onitsha Market Literature sub-genre.

- Burna Boy, the Spotlight, and the Cost of Arrogance - November 27, 2025

- Billionaires Conclave USA Brings Career Wealth Masterclass to Houston with Dr. Olumide Emmanuel - July 12, 2025

- OPINION: What Has Quality Got to Do With Soludo’s Made-in-Anambra Brands - February 5, 2022

-

Anthony Obi Ogbo18 hours ago

Anthony Obi Ogbo18 hours agoTexas’ 18th Congressional District Runoff: Amanda Edwards Deserves This Seat

-

Anthony Obi Ogbo5 days ago

Anthony Obi Ogbo5 days agoWhen Power Doesn’t Need Permission: Nigeria and the Collapse of a Gambian Coup Plot

-

Anthony Obi Ogbo3 weeks ago

Anthony Obi Ogbo3 weeks agoBurna Boy, the Spotlight, and the Cost of Arrogance

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoBizarre Epstein files reference to Trump, Putin, and oral sex with ‘Bubba’ draws scrutiny in Congress

-

Lifestyle1 month ago

Lifestyle1 month agoKaduna Governor Commissions Nigeria’s First 100-Building Prefabricated Housing Estate

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoUSDA head says ‘everyone’ on SNAP will now have to reapply

-

News1 month ago

News1 month agoTrump orders Bondi to investigate Epstein’s ties to Clinton and other political foes

-

Africa5 days ago

Africa5 days agoNigeria–Burkina Faso Rift: Military Power, Mistrust, and a Region Out of Balance